By RFE/RL

March 11, 2015

"The United States has issued a new list of individuals and entities to be sanctioned over Russia's interference in Ukraine, including Kremlin-connected nationalist ideologue Aleksandr Dugin and former Ukrainian Prime Minister Mykola Azarov.

"The Treasury Department on March 11 also sanctioned a bank in Crimea -- the Russian National Commercial Bank -- two other former officials from the government of ousted Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, eight Ukrainian separatists, and two other leaders of Dugin's Eurasian Youth Union.

"Any U.S. property held by those individuals is frozen, and U.S. citizens are prohibited from doing business with them. The United States took the action to "hold accountable those responsible for violations of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity." Russian FSB chief Aleksandr Bortnikov, who has been targeted by sanctions in the EU and Canada, was not on the list of individuals targeted by the Treasury Department in this latest round of sanctions."

Wednesday, March 11, 2015

Friday, February 27, 2015

Houellebecq and Guénon

Soumission (Submission), the new novel by the controversial and best-selling French novelist Michel Houellebecq, has been widely identified (especially in the English-language press) as Islamophobic, but might better be described as Traditionalist.

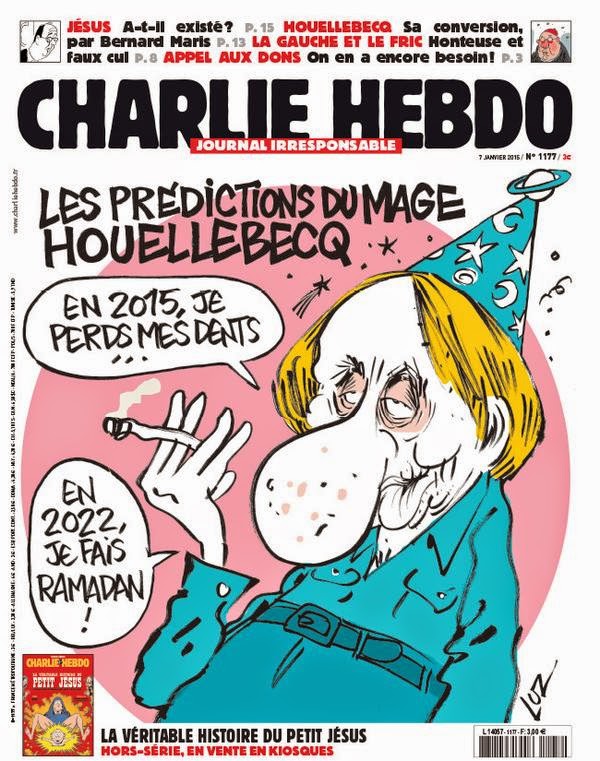

Soumission (Submission), the new novel by the controversial and best-selling French novelist Michel Houellebecq, has been widely identified (especially in the English-language press) as Islamophobic, but might better be described as Traditionalist.Houellebec and Soumission were featured on the January 7, 2015 cover of Charlie Hebdo (shown here). Houellebecq's novel was selling well even before the Charlie Hebdo cover and attacks, has since become even better known, and is due out soon in English translation.

Perhaps the book's incidental link to Charlie Hebdo helps explain its identification as Islamophobic. The book certainly features the election of an Islamist as president of France and the consequent Islamization of some aspects of French life, a scenario reminiscent of the Eurabia about which writers such as Bat Ye'or have been warning. However, these events are not the book's main subject. National political events are the background against which the book tells its real story.

The book's real story is the decline and redemption of the narrator, François, a literature professor and expert on Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907), author of À rebours (1884). The novels of Huysmans are partly autobiographical, and the redemption of Huysmans was found in Catholicism. The story of Houellebecq's hero François evidently echoes some aspects of the life of Houellebecq himself, and certainly echoes Huysmans. The difference is that François finds his redemption in Islam. And his path to Islam runs through identitarian Traditionalism.

Two of the book's characters are or have been involved in the mouvement identitaire, the "identitarian movement." Houellebecq does not explain this movement, but it will be familiar to some readers of this blog as that section of the New Right that emphasizes traditional cultural identities (as against globalized multiculturalism), is partly inspired by Traditionalism, has been further developed by thinkers such as Alain de Benoist and Guillaume Faye, and acknowledges Alexander Dugin. Both of Houellebecq's characters with connections to the identitarian movement are presented sympathetically. One, Robert Rediger, is a major character in the book, the Islamist president of the Sorbonne and later a minister in the Islamist government of France.

Houellebecq's Rediger wrote his PhD thesis on Guénon and Nietzsche, and converted to Islam when he concluded that Catholicism had lost the power to regenerate a fallen West, and that the future lay in Islam, as Guénon had shown. These ideas are developed at some length in Soumission, and are the book's philosophical heart. They are simplified Traditionalism: Traditionalism because they acknowledge Guénon and identify modernity as decline and tradition as the solution, and simplified because they make no mention of perennialism or of the esoteric. Houellebecq's Guénon was a convert to Islam, not a Sufi.

In the end, the real topic of Soumission is probably the decline of the West, and specifically of the French Left, not Islam. Houellebecq does not in fact seem particularly interested in Islam, which he seems to understand primarily in terms of polygamy. Houellebecq's Islam does not stop anyone from drinking good wine. His book, however, shows how Guénon's work is assuming new relevance as Europe's political landscape changes.

My thanks to Bertrand for drawing my attention to Bouddhanar's post "Michel Houellebeck lecteur de René Guénon" and thus to the Traditionalist content of Soumission.

Thursday, January 29, 2015

Dugin and Kotzias

Questions are being raised (for example, in the FT) about relations between Alexander Dugin (right in photo) and the new Greek foreign minister, Nikos Kotzias, (left in photo). Kotzias, a Communist in his student days and then a successful professor of international studies before his appointment as foreign minister, hosted Dugin at the University of Piraeus in 2013. The transcript of this event tells us little of the views of Kotzias, who chaired the session and said little, other than to compare the European Union to an empire. That Kotzias is hostile to the European Union and its recent policies regarding Greece should come as no surprise: that is after all the whole point of the elections that have just brought Kotzias and colleagues to power.

Questions are being raised (for example, in the FT) about relations between Alexander Dugin (right in photo) and the new Greek foreign minister, Nikos Kotzias, (left in photo). Kotzias, a Communist in his student days and then a successful professor of international studies before his appointment as foreign minister, hosted Dugin at the University of Piraeus in 2013. The transcript of this event tells us little of the views of Kotzias, who chaired the session and said little, other than to compare the European Union to an empire. That Kotzias is hostile to the European Union and its recent policies regarding Greece should come as no surprise: that is after all the whole point of the elections that have just brought Kotzias and colleagues to power.There are signs of Kotzias and colleagues inclining towards Russia, including Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras choosing the Russian ambassador as the first foreign official he met after his appointment, and the stance he is adopting against EU sanctions against Russia. There are, however, no obvious signs of them tending specifically towards Dugin's version of Eurasianism, and The Economist is probably right to conclude that "there is no basis for religious determinism in diplomatic history... [but] when the diplomatic stars are aligned, common cultural and spiritual reference points can give added resonance to a relationship."

Saturday, January 03, 2015

The Kali yuga in context

As readers of Guénon well know, the concept of the kali yuga or dark age is central to his thought, and thus to Traditionalism as a whole. An excellent new article on the Hindu origins and European uses of the concept places its development in a wider context. The article is Luis González-Reimann, "The Yugas: Their Importance in India and their Use by Western Intellectuals and Esoteric and New Age Writers," Religion Compass 8 (2014), pp. 357–370.

González-Reimann argues that the concept of the kali yuga is a late one, emerging in India only around the first century AD, when it helped to explain the various disasters then afflicting the classical Vedic system. It became known in Europe during the seventeenth century, but did not attract much attention until the eighteenth century, when Voltaire was among those interested in it, and in the challenge that the system of the yugas presented to established Christian chronology. The intellectual mainstream soon lost interest, however, according to González-Reimann because of the impact of a refutation by Sir William Jones. In fact, I suspect, it was also because chronologies based on geology were then beginning to render all other varieties of chronology obsolete.

Even if the intellectual mainstream lost interest in the yugas, esotericists did not. The yugas featured in the work of Antoine Fabre d'Olivet (1767-1825), who suggested that the Hindus had got them the wrong way round and that the kali yuga was actually the best of the four yugas. They then appear in the work of Alexandre Saint-Yves d'Alveydre (1842–1909), who agreed with Fabre d'Olivet that the yugas were actually improving. Helena Blavatsky, Annie Besant and Rudolf Steiner all wrote about the yugas, following Saint-Yves d'Alveydre's optimistic view. Besant emphasized the coming new age of the satya yuga, and Steiner even held that the kali yuga ended in 1899.

Saint-Yves d'Alveydre modified the standard Indian understanding of the yugas, equating the mahāyuga with the manvantara, two measures of time that classically belonged to different systems, and were far from identical. Guénon follows Saint-Yves d'Alveydre in this, which indicates his proximate source. Guénon differed from the esoteric norm, however, and most importantly, in reverting to the original emphasis on the negative nature of the kali yuga itself. And the rest, as they say, is history. Once again, we see how Traditionalism owes much to mainstream esotericism, but also differs from it.

All this is shown clearly by González-Reimann in his article, which closes by observing that "in the second half of the 20th century, esotericism largely morphed into New Age thinking, or ... the New Age engulfed esotericism. Either way, such ideas [as the yugas] ... have been incorporated into the manifold spectrum of New Age thought." Yes, perhaps, so far as optimistic understandings from Fabre d'Olivet and Saint-Yves d'Alveydre to Besant and Steiner are concerned, but no so far as the Traditionalist understanding is concerned.

González-Reimann argues that the concept of the kali yuga is a late one, emerging in India only around the first century AD, when it helped to explain the various disasters then afflicting the classical Vedic system. It became known in Europe during the seventeenth century, but did not attract much attention until the eighteenth century, when Voltaire was among those interested in it, and in the challenge that the system of the yugas presented to established Christian chronology. The intellectual mainstream soon lost interest, however, according to González-Reimann because of the impact of a refutation by Sir William Jones. In fact, I suspect, it was also because chronologies based on geology were then beginning to render all other varieties of chronology obsolete.

Even if the intellectual mainstream lost interest in the yugas, esotericists did not. The yugas featured in the work of Antoine Fabre d'Olivet (1767-1825), who suggested that the Hindus had got them the wrong way round and that the kali yuga was actually the best of the four yugas. They then appear in the work of Alexandre Saint-Yves d'Alveydre (1842–1909), who agreed with Fabre d'Olivet that the yugas were actually improving. Helena Blavatsky, Annie Besant and Rudolf Steiner all wrote about the yugas, following Saint-Yves d'Alveydre's optimistic view. Besant emphasized the coming new age of the satya yuga, and Steiner even held that the kali yuga ended in 1899.

Saint-Yves d'Alveydre modified the standard Indian understanding of the yugas, equating the mahāyuga with the manvantara, two measures of time that classically belonged to different systems, and were far from identical. Guénon follows Saint-Yves d'Alveydre in this, which indicates his proximate source. Guénon differed from the esoteric norm, however, and most importantly, in reverting to the original emphasis on the negative nature of the kali yuga itself. And the rest, as they say, is history. Once again, we see how Traditionalism owes much to mainstream esotericism, but also differs from it.

All this is shown clearly by González-Reimann in his article, which closes by observing that "in the second half of the 20th century, esotericism largely morphed into New Age thinking, or ... the New Age engulfed esotericism. Either way, such ideas [as the yugas] ... have been incorporated into the manifold spectrum of New Age thought." Yes, perhaps, so far as optimistic understandings from Fabre d'Olivet and Saint-Yves d'Alveydre to Besant and Steiner are concerned, but no so far as the Traditionalist understanding is concerned.

Sunday, December 21, 2014

Traditionalism as a Western adaptation of Hinduism that negates claims of Truth?

D.A. has drawn my attention to a review essay prompted by Against the Modern World that raises an interesting question: the review essay's author, Mohamed Ghilan, writes: "Traditionalism is a Western adaptation of Hinduism that negates claims of Truth by any religion through relativizing all of them."

I think Mohamed Ghilan is right in some ways and wrong in others. He is right in the sense that early Traditionalism drew very heavily on Hinduism (as did other religious currents in the West at the time). He is also right in that in general relativizing multiple religions inevitably negates the truth claims of any of them, since if all claims are true in some sense, none can be true literally. And he is right that in the case of Traditionalism, a focus on the esoteric may trivialise the exoteric, not exactly negating the truth claims of a given exoteric religion, but reducing their importance.

Mohamed Ghilan is wrong, though, in the sense that although early Traditionalism drew heavily on Hinduism, Hinduism was not its most important ingredient. I am not now quite sure what the most important ingredient was, but I am beginning to suspect that it was a development of Neoplatonic philosophy. Neoplatonism is of course found in classic Islamic philosophy (and thus also in Sufism) as well as in Western thought. Our understanding of the esoteric, both in Islam and in Western thought, owes much to Neoplatonism. Mohamed Ghilan may thus actually be joining the ancient dispute about the relationship between philosophy and religion, between the esoteric and the exoteric.

My own feeling is that philosophy and religion, the esoteric and the exoteric, are not necessarily incompatible. One can find a philosophical proposition convincing and still follow a religion, just as one can find a natural-scientific proposition convincing and still follow a religion. But one can also do the opposite, and focus on the esoteric to the full or partial exclusion of the exoteric. It depends on the person and on circumstances.

I think Mohamed Ghilan is right in some ways and wrong in others. He is right in the sense that early Traditionalism drew very heavily on Hinduism (as did other religious currents in the West at the time). He is also right in that in general relativizing multiple religions inevitably negates the truth claims of any of them, since if all claims are true in some sense, none can be true literally. And he is right that in the case of Traditionalism, a focus on the esoteric may trivialise the exoteric, not exactly negating the truth claims of a given exoteric religion, but reducing their importance.

Mohamed Ghilan is wrong, though, in the sense that although early Traditionalism drew heavily on Hinduism, Hinduism was not its most important ingredient. I am not now quite sure what the most important ingredient was, but I am beginning to suspect that it was a development of Neoplatonic philosophy. Neoplatonism is of course found in classic Islamic philosophy (and thus also in Sufism) as well as in Western thought. Our understanding of the esoteric, both in Islam and in Western thought, owes much to Neoplatonism. Mohamed Ghilan may thus actually be joining the ancient dispute about the relationship between philosophy and religion, between the esoteric and the exoteric.

My own feeling is that philosophy and religion, the esoteric and the exoteric, are not necessarily incompatible. One can find a philosophical proposition convincing and still follow a religion, just as one can find a natural-scientific proposition convincing and still follow a religion. But one can also do the opposite, and focus on the esoteric to the full or partial exclusion of the exoteric. It depends on the person and on circumstances.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)